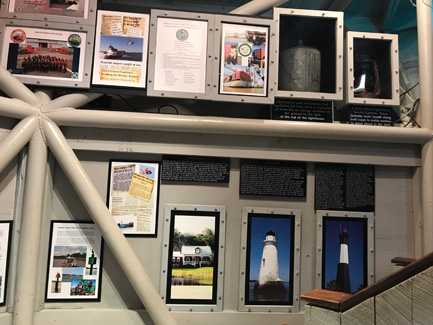

CLIMB THROUGH TIME – EXPLORE THE HISTORY OF THE ISLAND AND THE LIGHTHOUSE

Click on a level below for details on that level:

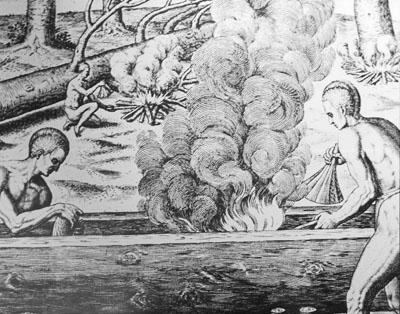

Hilton Head Island has been inhabited by human beings deep into the misty past of pre-history, perhaps 10,000 years ago and beyond. The first residents were early American Indians. They came because of the abundant food resources provided by the surrounding waters. These ancient peoples have left us evidence of their visits here, such as the mysterious Indian shell ring in the Sea Pines Forest Preserve. You can still find bits of their ancient, fiber-tempered pottery along the creek banks and beaches. These early inhabitants were called Yemassee Indians and were first recorded by the early European explorers.

Hilton Head Island has been inhabited by human beings deep into the misty past of pre-history, perhaps 10,000 years ago and beyond. The first residents were early American Indians. They came because of the abundant food resources provided by the surrounding waters. These ancient peoples have left us evidence of their visits here, such as the mysterious Indian shell ring in the Sea Pines Forest Preserve. You can still find bits of their ancient, fiber-tempered pottery along the creek banks and beaches. These early inhabitants were called Yemassee Indians and were first recorded by the early European explorers.  From the top of the Harbour Town Lighthouse, you can experience vistas similar to the sights that the great seamen of Europe must have seen when they first guided their ships in Calibogue Sound. You can see the shoreline of Spanish wells where the Spanish arrived first in 1521 under the lead of Captain Cordillo. Lucas De Ayllon, a fellow adventurer, established a settlement here of some 500 people in 1526, but it lasted only a short time and little is known of its existence.

From the top of the Harbour Town Lighthouse, you can experience vistas similar to the sights that the great seamen of Europe must have seen when they first guided their ships in Calibogue Sound. You can see the shoreline of Spanish wells where the Spanish arrived first in 1521 under the lead of Captain Cordillo. Lucas De Ayllon, a fellow adventurer, established a settlement here of some 500 people in 1526, but it lasted only a short time and little is known of its existence.

A century later in 1663, Captain William Hilton arrived on his ship, the Adventure, sailing out of the British territory of Barbados. Hilton had been sent to explore the lands that King Charles II had granted to eight of his chief supporters, the Lord Proprietors.

It was the result of this act that this region came to be known as “Carolina” in honor of King Charles. Captain Hilton found fresh water and game here and spoke most favorably of the island in his ship’s log. He marked it on his chart as “Hilton’s Head” because of a high bluff located in Hilton Head Plantation, now known as Dolphin Head. It could be easily recognized from the ocean approach to Port Royal Sound.

Our neighbor to the south, Georgia, became the thirteenth colony in 1733. Under the leadership of General James Oglethorpe it flourished, and Savannah became the major sea port on the Southeast Coast and America’s first planned city.

Our neighbor to the south, Georgia, became the thirteenth colony in 1733. Under the leadership of General James Oglethorpe it flourished, and Savannah became the major sea port on the Southeast Coast and America’s first planned city.

After 46 years of growth and prosperity, America declared its independence from England. The Revolutionary War came as a shock to the Lowcountry since most colonists still had close family ties in England. Fortunately, the resulting trade embargo did not include a restriction on colonists’ ability to export rice, so at least some commerce was still possible. However, as the battles raged, a convoy of British ships sailed up Skull Creek in January 1779, destroying homes and farms along the way (the convoy route can easily be seen from the top of the lighthouse). This brutal act galvanized islanders on the side of the revolution. These families who remained steadfastly loyal to the King fled to the Caribbean Islands of Barbados, St. Thomas, and St. Kitts where Hilton Head Island family names still persist.

Daufuskie residents, however, stayed loyal to the British Crown and made sporadic trips in rowboats across Calibogue Sound to raid island homes. Although the war ended at Yorktown in 1781, the rowboat raids continued across the sound for many months after the conflict had been resolved and we had become an independent nation. Those angry rowboat raiders might well have landed right at the foot of the lighthouse!

By 1728 the last of the Yemassee Indians were driven south into the Florida Everglades. A famed Indian fighter that Colonel John Barnwell nicknamed “Tuscarora Jack,” was granted 1,000 acres (about 1/5 the size of Sea Pines Plantation) and became the island’s first settler.

By 1728 the last of the Yemassee Indians were driven south into the Florida Everglades. A famed Indian fighter that Colonel John Barnwell nicknamed “Tuscarora Jack,” was granted 1,000 acres (about 1/5 the size of Sea Pines Plantation) and became the island’s first settler.

The rich natural resources on Hilton Head included the tall, straight sea pines used for masts and booms on the great British ships. The iron-hard live oaks were used for ships’ planking as well as pine pitch and tar for caulking. Later, the British would lament this remarkably hard oak as it was used on America’s great warship “Old Ironsides,” which repelled British cannonballs fired at her during the Revolutionary War.

By 1731, the first Royal Governor arrived to oversee the settlement, which set the stage for the evolution of rice and indigo crops that became the foundation of the wealthy plantation culture that followed.

South Carolina was the first state to secede from the Union over the issue of slavery.

South Carolina was the first state to secede from the Union over the issue of slavery.

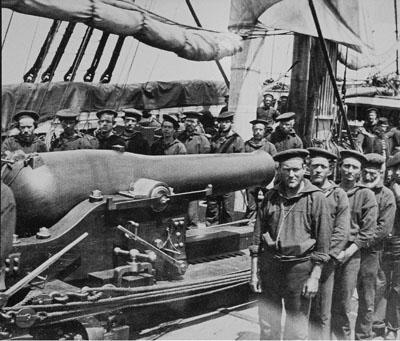

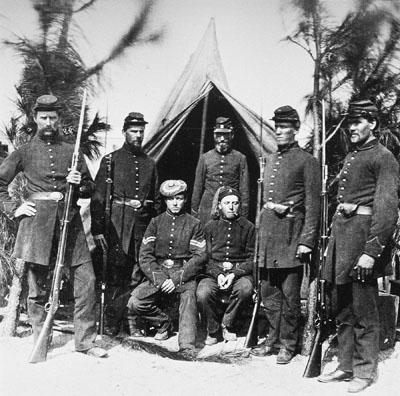

After the fall of Ft. Sumter to Union forces, President Lincoln developed a plan to blockade all Southern ports to prevent the Confederate forces from supplying its troops. Hilton Head Island became a strategic target for this blockade.

On November 7, 1861, the largest Naval and amphibious forces ever mounted to date entered Port Royal Sound and devastatingly bombarded Ft. Walker (now in Port Royal Plantation) and killed off the Confederate defenders. Over 12,600 federal troops invaded Hilton Head and effectively ended the Era of the Great Plantations.

During the Civil War the population of Hilton Head Island soared to over 50,000 soldiers, carpetbaggers, and hangers-on, as well as merchants who operated barbershops, a theater, a hotel, two newspapers, and various shady enterprises in an area that became known as “Robbers Row” just outside the fort. Men passed the time in surprisingly contemporary ways. Hilton Head Island was even the site of a baseball game attended by approximately 50,000 spectators.

During this time there were few battles. The strength of this outpost discouraged Confederate troops from launching an attack.

In 1790, shortly after the Revolutionary War, an island planter named William Elliott II grew his first crop of a “long-staple, silk- fibered, smooth-seeded cotton,” which quickly became known as “Sea Island” cotton. Almost overnight it brought great riches to those who planted it. The markets in Europe gobbled it up. The wealth these planters amassed from 1790 to 1825 made them among the richest families in early America!

In 1790, shortly after the Revolutionary War, an island planter named William Elliott II grew his first crop of a “long-staple, silk- fibered, smooth-seeded cotton,” which quickly became known as “Sea Island” cotton. Almost overnight it brought great riches to those who planted it. The markets in Europe gobbled it up. The wealth these planters amassed from 1790 to 1825 made them among the richest families in early America!

Growing this product required intensive labor; thus, the extensive use of slave labor flourished in these sea islands and Hilton Head as well. Hilton Head was the site of hard-working, productive farms owned by wealthy planters. They typically built grand homes away from the sea islands in climates cooler and safer from malaria than the Lowcountry plantations.

Seasons passed, families were built, great profits were amassed and the island persisted as it had for thousands of years before.

The end of the Civil War came as swiftly and dramatically as the beginning. In a matter of days, the troops were packed up and shipped off to their homes. The island was suddenly left alone. In the wake of the Civil War, Hilton Head was a population consisting primarily of freed slaves, many of whom were granted 30 acres and a mule. A few of the confiscated plantations were sold off for $1 per acre, some redeemed by their owners as payment of back taxes. During the subsequent quiet period, the Gullah culture flourished and blossomed into a Freedmen’s lifestyle.

The end of the Civil War came as swiftly and dramatically as the beginning. In a matter of days, the troops were packed up and shipped off to their homes. The island was suddenly left alone. In the wake of the Civil War, Hilton Head was a population consisting primarily of freed slaves, many of whom were granted 30 acres and a mule. A few of the confiscated plantations were sold off for $1 per acre, some redeemed by their owners as payment of back taxes. During the subsequent quiet period, the Gullah culture flourished and blossomed into a Freedmen’s lifestyle.

Native islanders (former slaves) took up subsistence farming and fishing while building neighborhoods, churches, and schools. Their language came to be known as “Gullah,” a language that survives today. In this culture, storytellers emerged, and legends as well as superstitions were taught.

This was an era of relative isolation and peace on the island. Their African heritage cast a long shadow on these islanders and all they did. In 1879, a now-famous journalist with the Atlanta Constitution started writing a column of folk tales he learned while living in the Lowcountry and working for the Savannah newspapers. He collected these tales under the title Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings. The journalist was, of course, Joel Chandler Harris. The stories became world famous and carried the spirit and wisdom of the Gullah people to the world.

After 1869, while Hilton Head Island slept under the warm Carolina sun, it became enriched by the Gullah culture but remained isolated from mainland culture. During the early 1940s, three families came into ownership of large tracts of land covering much of the island. These families formed a lumber cutting consortium and actively cut and barged Southern Pine to paper factories in Savannah and elsewhere. The island became a hunting and fishing paradise for Northern sportsmen.

After 1869, while Hilton Head Island slept under the warm Carolina sun, it became enriched by the Gullah culture but remained isolated from mainland culture. During the early 1940s, three families came into ownership of large tracts of land covering much of the island. These families formed a lumber cutting consortium and actively cut and barged Southern Pine to paper factories in Savannah and elsewhere. The island became a hunting and fishing paradise for Northern sportsmen.

But, in 1956, Hilton Head Island experienced another dramatic change. A swing bridge was constructed to the island, which spanned the Intracoastal Waterway. Suddenly it was no longer a slow ferryboat ride to the island, just a short trip over the bridge.

Entrepreneurs arrived. The Norris Richardson Company built the first grocery store near the ocean. Wilton Graves constructed the first modern lodging which he called the Sea Crest Motel. Charles Fraser, a young Yale Law School graduate, began to realize the vision he had formed years earlier during his family’s timbering days. His idea was to create on Hilton Head Island an environmentally friendly residential resort community. This dream took shape as Sea Pines Plantation. The magnitude and eventual result of the dream would shock even him. Almost in consort with Charles Fraser’s plans came the ideas of another island entrepreneur, Fred Hack. His plans for Port Royal Plantation reflected his love of history and his brother Orion’s love of nature.

The era of modern day Hilton Head Island effectively began with the 1956 bridge. Since that time, Charles Fraser initiated the process of crafting Sea Pines Plantation – the signature of which is the Harbour Town Lighthouse.

The era of modern day Hilton Head Island effectively began with the 1956 bridge. Since that time, Charles Fraser initiated the process of crafting Sea Pines Plantation – the signature of which is the Harbour Town Lighthouse.

His vision was based on protecting the natural beauty of the land – wrapping human environments within the natural landscape of this sea island rather than imposing man and his structures upon it. His ideas included: “No building taller than the tallest tree”; “Paint in natural earth tone colors”; “Make the oceanfront available to as many as possible, while disturbing as few as possible.”

Quite different than the developers of his era, Charles Fraser saw community building as a means of preserving the land as well as opening it up for human habitation. To this end, he looked at the property as a whole, carefully noting the natural elements that must be protected. The largest surviving trees were protected from the land-clearing process; lot lines and street plans often were cut around trees rather than through them. At a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars, the Great Oak known as the “Liberty Oak,” that can be seen jutting into the harbor at Harbour Town, is a prime example of his reverence for the land. He also saw the importance of the unique story that Hilton Head Island and, in particular, Sea Pines Plantation have to tell. The little Gullah graveyard dating back to the slavery period, still used by native island families, is a good example. Tucked between some million dollar town homes framing the 18th fairway, the graveyard is still available to descendants of the original families for visits and burials.

Fraser’s development plan preserved substantial acreage dedicated to “Open Space” or nature preserves. In the 650-acre Sea Pines Forest Preserve, there are delightful nature walks and trails that enable residents and visitors to experience the island’s remarkable, subtropical beauty as it was seen by the early explorers. Within Sea Pines, several areas have been protected and are open for visitors to freely explore including the Tabby Ruins of the Baynard Plantation “Great House” and the ghostly but beautiful ruins of the rows of slave cabins.

Thanks to Charles Fraser’s responsible and careful development plan, it takes very little effort to enjoy the abundant wildlife that has been a part of the island environment for hundreds of years. White-tailed deer, raccoon, possum, otter, and even mink inhabit the wooded and marshland landscape. Additionally, Hilton Head is a bird watcher’s paradise with hundreds of species recognized as regular visitors and year-round residents. The ancient owner of the ponds and brackish waterways, the alligator, is always sleeping in the sun on warm days except during the chilly winter months when he retreats to his den for a season of hibernation. The surrounding ocean is richly populated with succulent Blue-claw Crabs, oysters, and shrimp, not to mention dozens of varieties of fish. The Atlantic bottlenose dolphin frolic all around the island as well as the occasional manatee. Yes, there are sharks too, and at certain times of the year jelly fish wash up on the beach along with a variety of shells and starfish.

By the way, if any creature you encounter has signs of still being alive, please return it to the ocean. Every creature serves an important purpose in the balance of nature in this area. Even with a current permanent population of over 35,000 people, Hilton Head Island and Sea Pines Plantation are still a nature lover’s dream.

CHARLES FRASER AND SEA PINES PLANTATION

CHARLES FRASER AND SEA PINES PLANTATION

A little known part of this island’s history to visitors and residents alike when viewing this community, so brightly punctuated by the lighthouse, is that Charles Fraser’s vision for community building reverberated throughout the world. The idea that one could preserve the essential character of the land by developing it was entirely new to the cost-conscious development community.

Fraser’s “Highest and Best Use” concept required large tracts of protected land, or “open space.” True, this land might have provided room for more houses or condominiums, but the essential character of the land would have been lost. “Highest and Best Use” meant finding ways to allow people to enjoy the natural beauty special to Hilton Head Island.

Fraser established the concept of an architectural review board comprised of professional architects and planners as well as residents. This board still convenes regularly to review house plans for new residences and has the power to adjust and even reject designs that would harm the neighborhoods they are planned for. At first controversial, review boards are now a part of community planning nationwide.

By building golf courses, Fraser attracted players and buyers, but he also opened up air corridors to feed fresh air into the dense maritime forests. Sea Pines became a mecca for golf and tennis facilities. The first condominium laws in South Carolina were drafted for the Beach Lagoon Villas, the earliest attached housing in the state.

CHARLES FRASER AND FRIEND MAKE THE NEWS AGAIN!

Fraser’s dream grew into a community that is nationally televised each year, one that attracts over two million visitors annually while retaining the privacy and exclusivity that is unique to Sea Pines. And, of course, with fame comes property appreciation. The ocean front lot that might have sold for $12,000 in 1957 would easily top $2 million today. Sea Pines set the tone for all of Hilton Head Island and hundreds of other community developments the world over. Sea Pines Plantation is, in fact, the only community to win the Urban Land Institute Award for Excellence twice in the same decade.

The crowning achievement of his planning and design expertise is often thought to be Harbour Town itself. As he saw it, he had a vision of an intimate Harbour Village with Lowcountry ambiance seasoned with the influence of the small distinctive harbors along the coast of southern France and Italy. He took his top design team to Europe and flew over dozens of small, enclosed harbors, taking the best features of them all and created a Southern version of Portofino, Italy. Harbour Town thus became a combination of shops, restaurants, and harborage beautifully accented by the candy striped lighthouse. From the top of the lighthouse, you can see a masterpiece of design and a community within a community, human in scale and delightful to the senses.

The crowning achievement of his planning and design expertise is often thought to be Harbour Town itself. As he saw it, he had a vision of an intimate Harbour Village with Lowcountry ambiance seasoned with the influence of the small distinctive harbors along the coast of southern France and Italy. He took his top design team to Europe and flew over dozens of small, enclosed harbors, taking the best features of them all and created a Southern version of Portofino, Italy. Harbour Town thus became a combination of shops, restaurants, and harborage beautifully accented by the candy striped lighthouse. From the top of the lighthouse, you can see a masterpiece of design and a community within a community, human in scale and delightful to the senses.

Sea Pines Plantation’s design is remarkably subtle. It is actually a series of distinct neighborhoods co-existing comfortably together. Areas of modest homes blend in with areas of condominiums and attached housing. These, in turn, are located adjacent to areas of larger lots and more substantial residences, which blend in with pockets of signature homes. In nearly every neighborhood, residences face views of ponds, wooded acreage, golf course vistas, sea marsh, or ocean front. The community combines shopping, dining, recreation, schools, a hotel, private clubs, picnic areas, historic sites, and large natural areas that are alternately vibrant with activity or quietly at peace, but always pristine and elegant. The community’s ability to preserve the best of its natural beauty within the preserve is something that should be not be missed.

This is not an accident. It is all the result of a plan that evolved from the simple principle of reverence for the natural resources of the land and a knowledge that human beings do not have to destroy a place in which they live. Little details such as minimal night lighting, informal street structure, shared access to the beach, significant tree preservation, and subtle color palettes for homes create a visual harmony that sets the standard for resort/residential development around the world. The simple and basic idea of placing living areas of a home on the side with the best view changed the way entire communities have been designed since the 1950s. Charles Fraser and his remarkably youthful team of planners and project managers can take a lion’s share of the credit for the revolutionary planning that Sea Pines Plantation initiated.

In 1968, selected sports writers and golf periodicals received telegrams announcing a new tournament to be called “The Heritage Classic.” It was described as the first major professional golf tournament to be held directly on the Atlantic sea coast. As the telegrams went out, builders were working feverishly to prepare the new course in Sea Pines by famed golf course architect Pete Dye in consultation with one of the tour’s hottest young players, Jack Nicklaus.

It was called the Harbour Town Golf Links, celebrating the location directly across from the harbor with a spectacular finishing 18th hole played directly toward the lighthouse. The editors of Golf Digest first described the 18th as “Horribly treacherous, a hole that deserves a graveyard, but easily as spectacular as Pebble Beach.”

Charles Fraser’s canny marketing ability came into play when he engaged Jack Nicklaus to assist rising star Pete Dye in the design. Together they invited Arnold Palmer to play in the first tournament. This trio of high-profile golf celebrities immediately intrigued the tour players and the media. What were they doing down there in an unknown place in South Carolina?

THE GREAT ARNOLD PALMER WINS! PALMER WON THE VERY FIRST HERITAGE AND SET THE TONE OF ONE OF THE PGA TOUR’S GREAT EVENTS UNDER THE SHADOW OF THE LIGHTHOUSE

THE GREAT ARNOLD PALMER WINS! PALMER WON THE VERY FIRST HERITAGE AND SET THE TONE OF ONE OF THE PGA TOUR’S GREAT EVENTS UNDER THE SHADOW OF THE LIGHTHOUSE

But Charles Fraser didn’t stop there. A well schooled historian, he performed extensive research on the history of golf in South Carolina and learned that there had been a charter for South Carolina’s first golf club dating back to colonial times. He further found that it was unused in modern times. Immediately he enacted legal proceedings to acquire the charter from the archives in Charleston and have it transferred to his new club at Harbour Town. This, the panache of the words “Heritage of Golf” became attached to the tournament name because the club operated under the charter of the state’s Inaugural Club and, in fact, one of the first in the country.

A singular Scottish plaid was assigned to the Winner’s Jacket by Fraser. This plaid winner’s jacket, the dramatic march of the bagpipers, and the traditional firing of the cannon became part of the backdrop for the tournament from the very start, making it as colorful and ceremonial an event as any on the tour.

THE LATE, GREAT PAYNE STEWART ON THE WAY TO HIS FIRST CHAMPIONSHIP AT HARBOUR TOWN IN 1989

THE LATE, GREAT PAYNE STEWART ON THE WAY TO HIS FIRST CHAMPIONSHIP AT HARBOUR TOWN IN 1989

The tournament became a national event due to the first winner …Arnold Palmer. Coming off a long slump, Arnie was back! And his Army was with him. The rest is legend. The champion’s list reads like a Who’s Who of Golf including Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Hale Irwin, Hubert Green, Tom Watson, Davis Love III, Payne Stewart, and Greg Norman–to name just a few. A complete list of all the winners and their scores is posted in the Harbour Town Clubhouse along with other memorabilia from the first, grand tournament.

As you look up the 18th fairway that hugs the shoreline of Calibogue Sound, you will notice the small peninsula that provides an alternate landing area for the tee shot creating a short cut to the green. This artful bit of design is actually the result of an accident. While the harbor was being dredged, a pipe broke loose and before the repair could be made it pumped enough sediment to create the peninsula. When Pete Dye saw what had happened his face lit up. “Perfect!” He said, “Why didn’t I think of that? Don’t touch it!” So it has remained the golfer’s temptation, and often downfall, since that time.

If you love golf…well, you’ve got to play Harbour Town. And if you love beautiful landscape architecture, take a walk on the 18 holes of one of America’s top twenty courses and see for yourself what a masterpiece it is.

It is fitting that this lighthouse at Harbour Town has come to be the symbol of Sea Pines Plantation, a community that has been designed around the comfort and safety of its inhabitants.

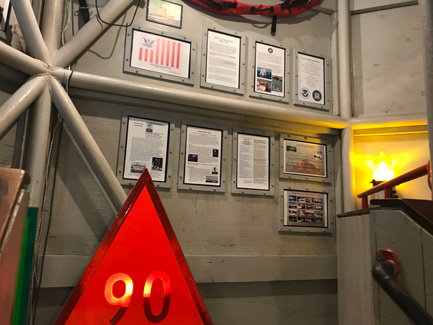

The Harbour Town Lighthouse, at ninety feet above Calibogue Sound, is the first privately funded lighthouse to be built in this area since the early 1800s. Although it was never meant to be an official navigational light, it has helped many a boater find safe passage through the fog back to Harbour Town. Completed in 1970, its distinctive candy striped octagon image has been broadcast the world over during the televised World Com Classic, rising up the famed 18th green of Harbour Town Golf Links.

HARBOUR TOWN LIGHTHOUSE

HARBOUR TOWN LIGHTHOUSE

Hilton Head has two lighthouses: the world-famous Harbour Town Lighthouse and a lesser recognized structure located in Palmetto Dunes Resort known as the 1880 Hilton Head Rear Range Light. The rear range light was a skeleton tower built by the U.S. Lighthouse Service and it was also known as the “Leamington Light.” It now graces one of the golf courses inside the plantation property. This is Hilton Head Island’s first light station, which originally consisted of two range lights–one atop the 95-foot skeleton tower and the other atop a front range light, which was a shorter structure located a mile away and could be moved as the shoals shifted. It was the difficult task of the lighthouse keeper to check on the movement of the sandy shoals that approached the island and position the movable structure so that it aligned with the rear range light for mariners to gain a safe passage through the channel. The hexagonal lantern room of the Hilton Head Rear Range Light was reached by climbing 114 steps in the central tower to the lantern where the light from kerosene lamps were intensified by a Fresnel lens and its hundreds of prisms. When lit, the rear range light was visible for approximately 15 miles out to sea. First commissioned in 1880, these range lights were taken out of service in 1932 and a modern, decorative light was installed in the skeleton tower. The two original lighthouse keepers’ cottages, said to be haunted, were moved to Harbour Town in the mid-1970s to preserve them.

Just across the sound from the Harbour Town Lighthouse, you can get a glimpse of one of the Daufuskie Lights, known as the Haig Point Range Light. It was one of two range lights situated on Daufuskie Island that worked together like the Hilton Head Rear and Front Range Lights. The Haig Point Range Lights were built in 1872; the rear range light was a combination of a lighthouse built on the keeper’s cottage. The light atop the keeper’s cottage rose to a height of 25 feet and was powered by a fifth order Fresnel lens with kerosene lamps in the center of the lens. The front range light was set on a pole far out in the water that aligned with the rear range light to show mariners a safe passage through the channel. Later a second structure was built that could be moved to direct boats to the channel. The front range light had to be movable to adjust for the movement of the soft-bottomed shallows. The charming little cottage is now used for guest lodging and special functions by the Haig Point Development, an exclusive residential community built by International Paper Company.

Just across the sound from the Harbour Town Lighthouse, you can get a glimpse of one of the Daufuskie Lights, known as the Haig Point Range Light. It was one of two range lights situated on Daufuskie Island that worked together like the Hilton Head Rear and Front Range Lights. The Haig Point Range Lights were built in 1872; the rear range light was a combination of a lighthouse built on the keeper’s cottage. The light atop the keeper’s cottage rose to a height of 25 feet and was powered by a fifth order Fresnel lens with kerosene lamps in the center of the lens. The front range light was set on a pole far out in the water that aligned with the rear range light to show mariners a safe passage through the channel. Later a second structure was built that could be moved to direct boats to the channel. The front range light had to be movable to adjust for the movement of the soft-bottomed shallows. The charming little cottage is now used for guest lodging and special functions by the Haig Point Development, an exclusive residential community built by International Paper Company.

Further to the east, around the other side of the island, a similar set of range lights were placed on what came to be called Bloody Point Bar in 1883. This ghoulish name grew out of what history recounts as being the site of a horrific Indian massacre. The massacre effectively signaled the end of the presence of the Yemassee Indians in this area. The cottage that was used as the rear range light has been pulled off of its original site and is no longer in use. Both of these range lights were deactivated in 1934. It is hard to imagine today how difficult the lighthouse keepers’ job must have been to row out in all manner of weather and keep the lamp lit on the poles located offshore.